Circadian rhythms rely on cell-autonomous clocks that control the rhythmic expression of a large number of genes. The core of eukaryotic circadian clocks consists of a negative feedback loop. The main clock components are known and their interactions have been demonstrated in many cases. However, it is not clear how these proteins measure time at the molecular level.

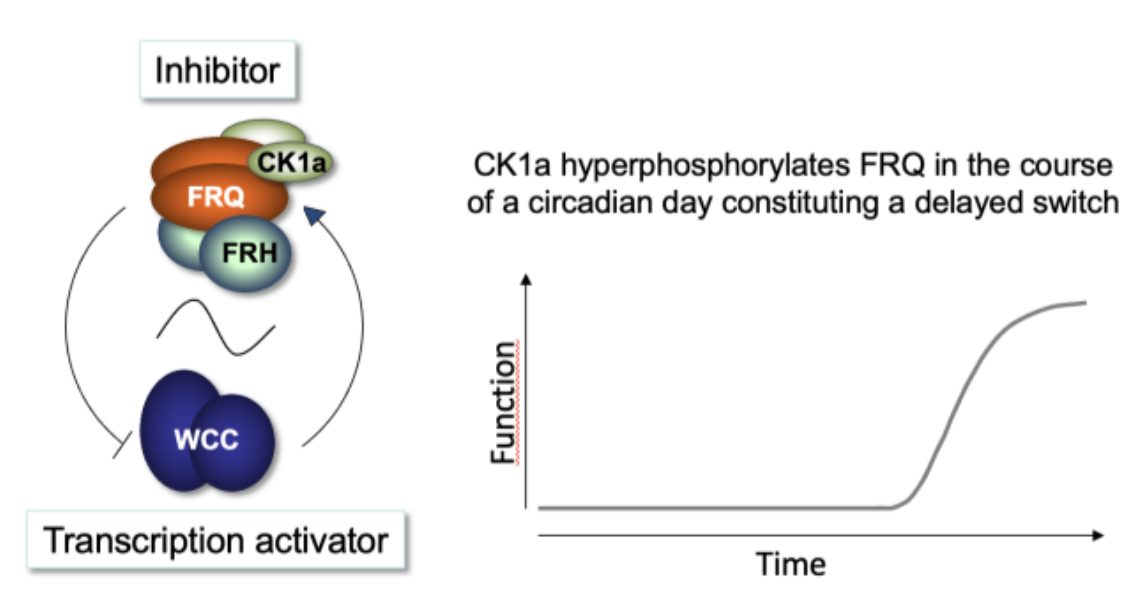

The frequency gene (frq) is a key element of the circadian clock of Neurospora (Fig. 1). Expression of frq is rhythmically controlled by the transcription factor WCC. FRQ, together with casein kinase 1a (CK1a) and FRQ-interacting RNA helicase (FRH), form the FFC complex. The FFC transiently interacts with WCC allowing CK1a to phosphorylate and inactivate WCC and thereby inhibiting frq RNA synthesis. Over the course of a day, FRQ becomes increasingly phosphorylated by CK1a, leading to its inactivation and degradation, and the onset of a new circadian cycle1. Progressive hyperphosphorylation of FRQ is associated with circadian timekeeping.

To elucidate how these molecules measure time, we recently showed that CK1a and FRQ form a timing module that supports slowly progressing hyperphosphorylation of FRQ on a circadian time scale in a temperature-compensated manner2,3. However, the conformational changes and associated functional changes induced by multisite phosphorylation of FRQ are not yet known and will be investigated in the upcoming funding period.

FRQ is a dimer and consists largely of intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs). Predictions by AlphaFold2 suggest that the N-terminal dimerization domain of FRQ serves as a hub that organizes IDRs into a distinct loop via long-range β−sheet interactions. The loop is divided into smaller loops by a long-range interaction of elements that form a CK1a-binding domain. The organization into loops promotes a compact conformation of FRQ. Each loop contains a cluster of phosphorylation sites. Interestingly, the conformational organization predicted in an unbiased manner bring two verified nuclear localization signals of FRQ into spatial proximity, which are separated in the primary sequence by about 450 amino acid residues. We will investigate how phosphorylation of sites in these clusters affects the conformational organization of FRQ and the accessibility of its NLSs. Molecular dynamics simulations identified sites critical for the organization of long-range β−sheet interactions and the assembly of the CK1a-binding domain. Preliminary data show that mutations of these sites lead to circadian arrhythmicity in vivo. We will use Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based analyses to study the organization of FRQ in loops and characterize the dynamics of conformational changes in response to phosphorylation. We hypothesize that phosphorylation of these clusters triggers with a time 179A16 Brunner / Milles delay a molecular switch that affects the conformation and potentially oligomeric state of FRQ, thereby timing its interaction with CK1a, WCC, nuclear shuttling, and degradation.

Fig. 1 Schematic of the circadian clock of Neurospora WCC is the central transcription factor of the circadian clock of Neurospora. WCC controls the rhythmic transcription of FRQ and the expression of the FRQ protein, which

associates with FRH and CK1a to form an inhibitory complex. FRH protects FRQ from premature degradation. The complex interacts with WCC, and CK1a phosphorylates WCC, thereby inactivating it, resulting in negative feedback from FRQ to its own transcription. Over the course of a circadian period, CK1a bound to the complex increasingly hyperphosphorylates FRQ, leading to its inactivation and degradation. Subsequent reactivation of WCC by phosphatases initiates the onset of a new circadian cycle.